Posted on: August 19, 2024, 11:15h.

Last updated on: August 19, 2024, 11:18h.

Dorothy, Scarecrow, Cowardly Lion and Tin Man were the wax figures guests expected to see while following the yellow brick road through the MGM Grand beginning in December 1993. That’s when Kirk Kekorian’s newly relocated resort, proudly boasting its ownership of all MGM movie rights, recreated the Emerald Forest smack in the middle of its casino.

But travelers on that road received a surprise when they passed the first bar on the right. Something called out them. It wasn’t the magic talking trees but something stranger.

An animatronic Foster Brooks sprang to life, every half hour, to lip-sync to a 20-minute live comedy set recorded by the real Brooks decades earlier.

“I said, ‘I’m gonna buy a condominium,’” the robot mimed along to the recording. “She said, ‘I don’t care, I’m going to take a pill anyway.’”

The Other Tin Man

So WTF was an animatronic Foster Brooks doing in the Emerald Forest? And why, of all the entertainers that a multimillion-dollar entertainment corporation could have immortalized at a Las Vegas bar in 1993 — from Dean Martin to Dudley Moore to anyone from “Cheers” — did it choose Foster Brooks for the animatronic treatment?

We’ll have all the answers for you shortly. But first, please congratulate yourself for reading this. Your curiosity is definitely not mainstream. As someone from the theme park podcast @PodcastTheRide tweeted last year: “If you’re in the market for a new Most Obscure Reference On Earth, try the Foster Brooks drunken animatronic in the MGM Grand lobby bar.”

And that’s a definition of obscure from someone who records podcasts about theme parks.

“The Foster Brooks robot is like the Nedra Harrison of robots,” noted “SpongeBob SquarePants” writer Jack Pendarvis in his 2008 Blogspot blog. “Neglected by our culture! Why does the lack of Foster Brooks robot information depress me?”

Well, Jack, here you go. We suppose 16 years late is better than never.

By the way, because we didn’t know, either, Nedra “Kewpie” Harrison served as the basis for the Dragon Lady in the 1939 comic strip “Terry and the Pirates,” a model for Salvador Dali paintings, and an undercover agent for the OSS during World War II — though, if you Google “Nedra Harrison” today, the first page and a half of results identify a surgeon in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Who the Hell Was Foster Brooks?

Pendarvis nailed it on the head in just two sentences: “Foster Brooks was a comedian who pretended to be a drunkard. That was his whole act.”

“The Loveable Lush” (his self-applied nickname as well as the title of his 1973 album) told sub-hysterical jokes to nightclub audiences, talk-show hosts and Dean Martin Roast daises while mumbling and hiccupping through a fake fog of inebriation.

One of the biggest laughs Brooks always got came from mentioning the name of the organization he founded: “Alcoholics Unanimous.”

But perhaps the funniest thing about Brooks was this fact unknown to his casual fans: he quit drinking in 1964.

How this guy ended up having a successful comedy career is something you should never try explaining to a member of Gen Z. It’ll just make us look bad.

But it all started with Steve Allen. The first host of “The Tonight Show” heard the former Louisville, Ky. TV morning man perform his drunk shtick and invited him on his talk show, which ran in syndication from 1962 to 1964.

Perry Como earns a blame assist for Brooks’ career. After the comedian’s drunk act cracked him up during a set at a North Carolina celebrity golf tournament, Como invited him to open for him at the International Hotel in 1969. The resort owners balked at Brooks’ advanced age and lack of fame, but Como insisted and they gave in.

You didn’t eff with Perry Como.

Brooks reportedly became the highest-paid opening act on the Strip, pulling down $40,000 per week to open for Robert Goulet, Buck Owens and Juliet Prowse at the Desert Inn and Frontier in the ’70s.

He also appeared regularly on “The Dean Martin Variety Show,” for which he won an Emmy nomination in 1974, and on several of the era’s sitcoms and game shows — always as the Loveable Lush.

His career had quieted significantly down by 1993, though, with occasional gigs paying him a reported $2,000 a pop. So when the MGM Grand offered him $10,000 a year — for 10 years — to license his likeness for the robot attraction, he was all in.

So Who’s to Blame for the Robot?

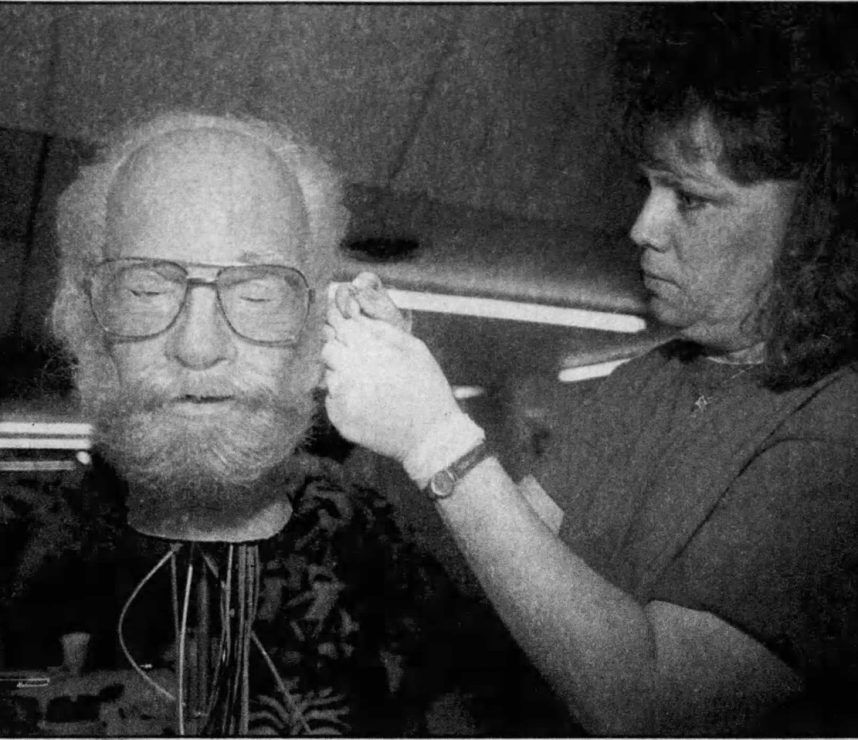

Not John Wood. He’s the very nice president and chair of Sally Dark Rides, the Jacksonville, Fla.-based theme park company that built the animatron 31 years ago.

Yes, we tracked Wood down, and his company’s work can still be found in Vegas. It designed the new “Spongebob Squarepants” attraction — callback alert! — at Circus Circus’ Adventuredome.

According to Wood, Fred Benninger commissioned the build simply because Brooks was one of his favorite comedians. It’s as simple as that.

Benninger, about 75 at the time, was the chair of MGM Grand Inc. And you try telling the chair of the corporation you work for that any idea he has is ridiculous.

“Fred really liked Foster Brooks and I was delighted that they needed some entertainment in the Betty Boop Lounge,” Wood told us.

The robo-holic, which sat at a little table roped off from the rest of the bar, took a reported $150,000 and 825 man-hours to build — though Wood said he doesn’t recall the specifics anymore and the records are no longer available to him.

Wood’s company did a great job making the thing, though, considering the technology of the day.

Its 30 lifelike movements were achieved with compressed air, so it sounded like a much-quieter auto repair shop whenever it swiveled in its chair. But it appeared totally lifelike. In fact, one night during the graveyard shift, a man, who was as tipsy as Brooks pretended to be, observed the robot with no apparent recognition that it wasn’t a real person.

At the end of the set, according a Betty Boop bartender, the guy left the robot a tip at its feet — apparently because it wouldn’t take the $2 from his hands.

Check out the Foster Brooks robot yourself in this 1995 video. It appears just after the 2 minute mark…

Meeting of the Brooks Brothers

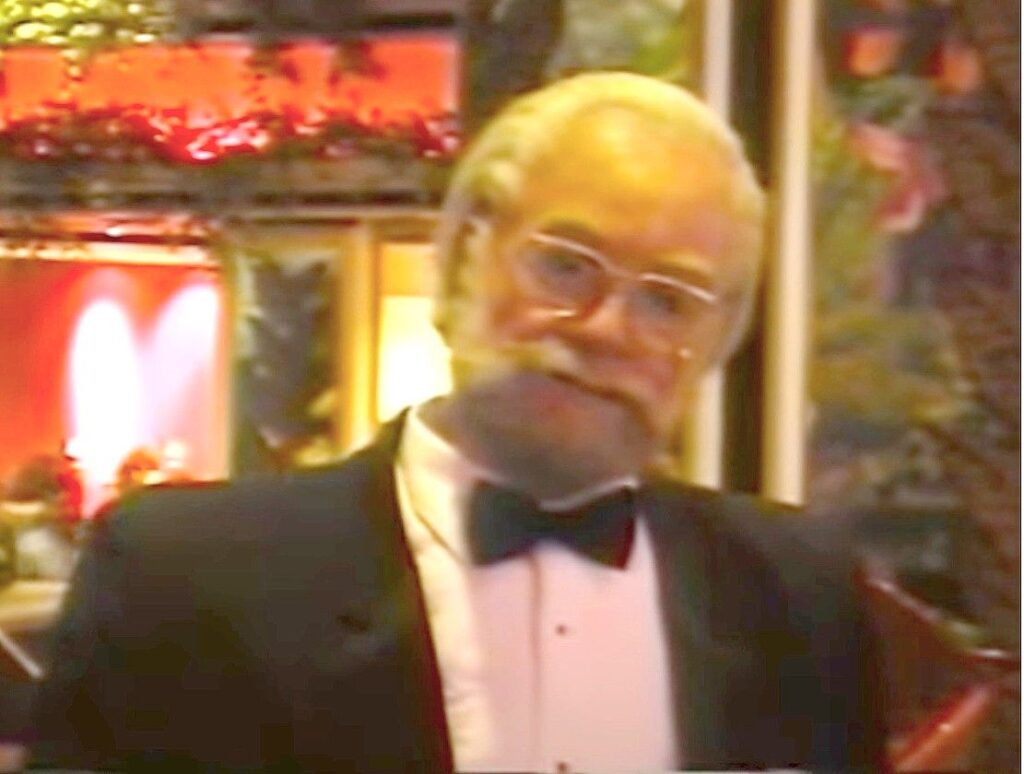

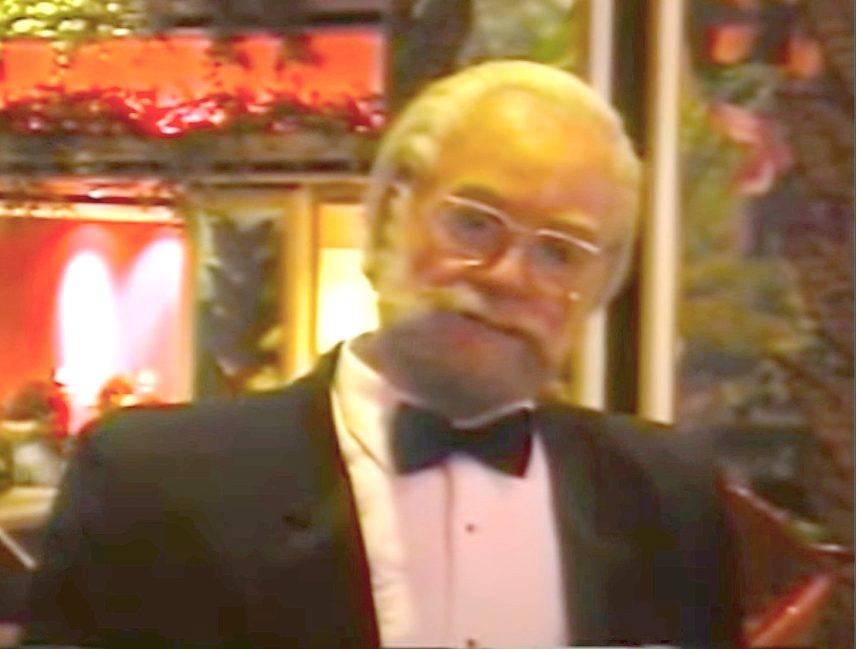

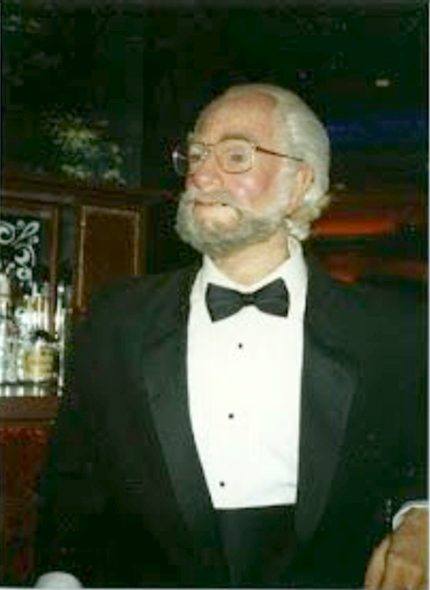

It was veteran Vegas entertainment journalist Mike Weatherford who hatched the inspired idea to take Brooks, who lived parttime in Las Vegas, to visit his rubber-coated counterpart for the first time in April 1994 and write about it for his column in the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

“I set it up and did it entirely on my own,” Weatherford told Casino.org. “And when I got hold of Foster Brooks, I was shocked that he hadn’t been there to see his robot before. I remember I had to go get him and pick him up at his house and drive him over there.”

Brooks, 81 at the time, walked slowly through the resort with a cane, due to a severe case of gout.

“I was feeling every painful step of it,” Weatherford recalled.

When the historic meeting took place, a small crowd gathered to watch.

This wasn’t necessarily because any of them knew who Foster Brooks was by 1994. Just as likely, they were drawn by the spectacle of a man observing his robotic twin as a professional photographer snapped photos.

Brooks stood speechless as he stared long and hard into the dead glass eyes of his replicant.

Finally, he announced, rather anticlimactically: “I look like an old man, which is what I am. It’s better than I’ll look when I’m dead, I guess.”

Terminated

Brooks’ figure was removed, along with the non-animated “Wizard of Oz” dummies, during a house-cleaning 1996-97 renovation. According to a couple of internet accounts, all the figures were in desperate need of repair and were just thrown out.

A much better story is the myth that the robot ticked off Mike Tyson, who KO’ed it to pieces before one of his bouts at the MGM Grand Garden — as though Tyson didn’t have anything better to do before a fight and could somehow have taken offense to a mute robot.

“I never heard that one,” Wood said, adding the revelation that tried to buy the robot back, but MGM wouldn’t sell it to him.

“Of course the license might have had something to do with that,” he said.

The real Brooks also wanted the robot when MGM was done with it, he told Weatherford, though that never happened. Brooks retired to Encino, Calif., where he died eight years into the robot’s 10-year contract, in 2001, at age 89.

It’s comforting to imagine the robot being discovered one day in a forgotten MGM warehouse or someone’s storage unit somewhere. Weatherford holds out hope for this.

“Somebody has it,” he said. “Anything with some curiosity value like that? I’m sure.”

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.