Posted on: January 26, 2024, 08:17h.

Last updated on: January 25, 2024, 05:02h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on Sept. 18, 2023.

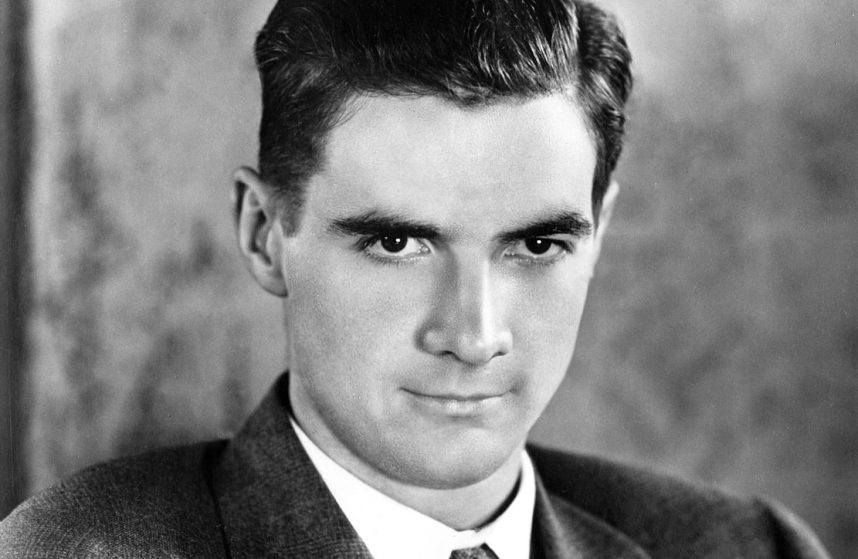

In 1967, billionaire Howard Hughes purchased the Desert Inn from Cleveland syndicate member Moe Dalitz just to avoid being evicted from his penthouse suite. Hughes found that he liked owning Las Vegas casino resorts. So he added the Sands, Frontier, Silver Slipper, Castaways, and Landmark to his new collection.

And this is what drove the mafia out of Las Vegas. Except, not really.

What drove the mafia out was mostly the Nevada Corporate Gaming Act of 1969.

This transformative legislation, an amendment to the Gaming Control Act, allowed corporations to own casinos by limiting licensure requirements to a few key executives. Before its passage, every single owner/shareholder had to be licensed.

On the 2021 podcast “Mobbed Up,” former US Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid called the Corporate Gaming Act “The salvation of Las Vegas.”

We’ve had a few bumps along the road, but, generally speaking, the corporate gaming act saved us,” Reid said shortly before his death.

By the way, Reid once served as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission (NGC), and in that role, he had a well-publicized run-in with Chicago oddsmaker Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal.

You might remember that incident from its dramatization in director Martin Scorsese’s 1995 movie, Casino, a screen-shot of which appears below.

Hughes Only Helped

Hughes helped diminish mob ownership by giving the bad guys six fewer Las Vegas Strip casinos to own for four years.

But, as Las Vegas Mob Museum VP of exhibits and Howard Hughes biographer Geoff Schumacher told Nevada Public Radio in 2016, “There is a lot of evidence that even after he bought a series of casinos on the Las Vegas Strip, that the mob was still skimming from the very casinos he had bought from them.”

In addition, mob ownership of competing casinos continued unabated while the former movie studio and airline mogul played Las Vegas hotelier.

Caesars Palace had just opened in 1966 thanks to a construction loan from the mob-connected Teamsters Union pension fund. When its owner, Jay Sarno, sold the property three years later amid a federal investigation into its financing, it went to Clifford and Stewart Perlman. According to the Mob Museum, they secretly used Miami mobster Meyer Lansky as a hidden investor.

Hughes tried to purchase Caesars Palace along with the Stardust and Riviera, but never closed those deals because of pressure from the federal government to halt his gaming purchases.

The year Hughes died, 1976, was also the year that Lefty Rosenthal took over the skim — stolen untaxed casino revenue — at the Stardust, Fremont, Marina, and Hacienda casinos.

So no, Hughes didn’t run the mob out of town.

Throwing the Book at ‘Em

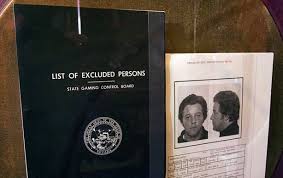

Just as influential as Hughes was the cumulative effect of the so-called “Black Book.” Created by Nevada gaming regulators in 1960, it’s the famous list of suspected mobsters, cheats, and others excluded from entering casinos in the state.

Officially called the Excluded Person List, it has included such names as Nick Civella, who once led the Kansas City crime family, former Chicago outfit boss Sam Giancana, and Tony “The Ant” Spilotro, a mob enforcer believed to be responsible for nearly two dozen murders.

By the ’80s, Nevada Governor Michael O’Callaghan helped extricate the residual mob influence from casino ownership. He did so by appointing members to the Nevada Gaming Control Board (NGCB) who would be more resistant to their bribes and threats.

But the mafia is actually still in Las Vegas. Though it no longer owns casinos, it can be found infiltrating side rackets such as illegal drugs, prostitution, money laundering, and loan sharking.

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. To read previously busted Vegas myths, visit VegasMythsBusted.com. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.