Posted on: December 16, 2024, 08:12h.

Last updated on: December 16, 2024, 07:24h.

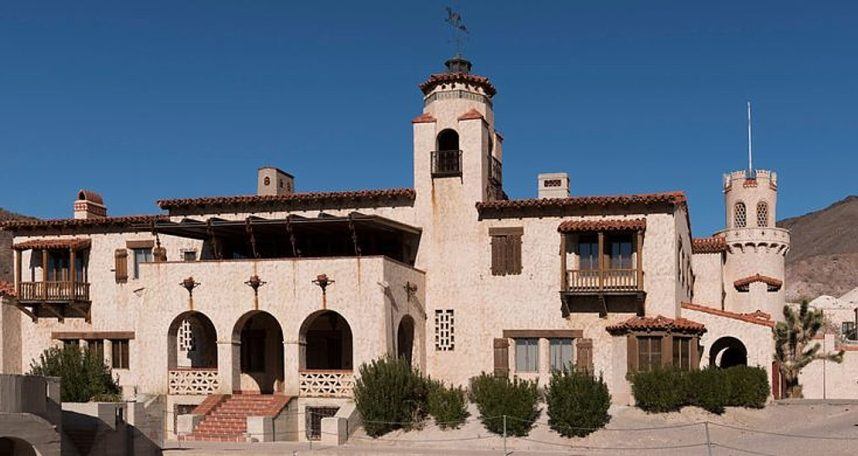

In the desert, three hours northwest of Las Vegas, stands a castle built by 1920s gold baron Walter Scott atop the secret gold mine that funded it. Except that nearly every word you just read is a lie.

Death Valley Ranch, almost universally called “Scotty’s Castle,” was built by Albert Johnson, a millionaire insurance broker from Chicago.

But you can be forgiven for believing the lie because it was perpetuated by both Scott and Johnson themselves.

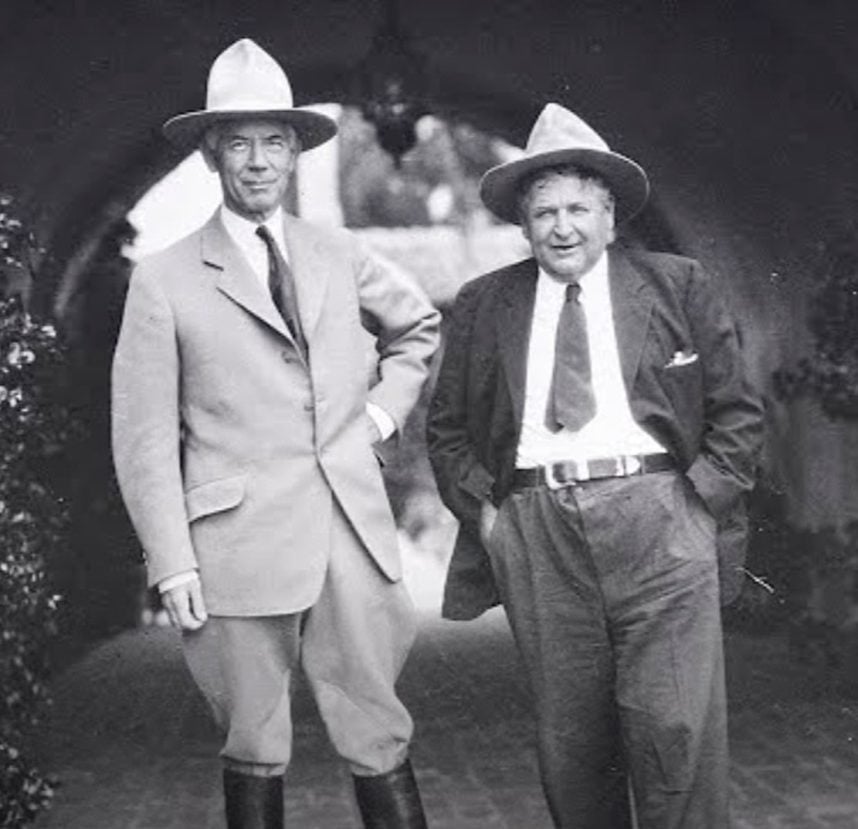

Scott, a horseman from Kentucky who once worked as a rough rider in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, was good at many things.

Lying like a dog was one of them.

Historian Richard Lingenfelter once described Scott as “a conscienceless con man, an almost pathological liar and a charismatic bullslinger” who was “willing to say or do anything for one more moment in the limelight.”

In fact, the only reason Johnson built “Scotty’s Castle” in the first place was because Scott had lied to him, convincing him to buy 1,500 acres in the middle of the hottest place on Earth based on false promises of a mine on the property that overflowed with gold.

By the way, it’s also not a castle — just a nice Spanish Colonial Revival villa with a couple of turrets.

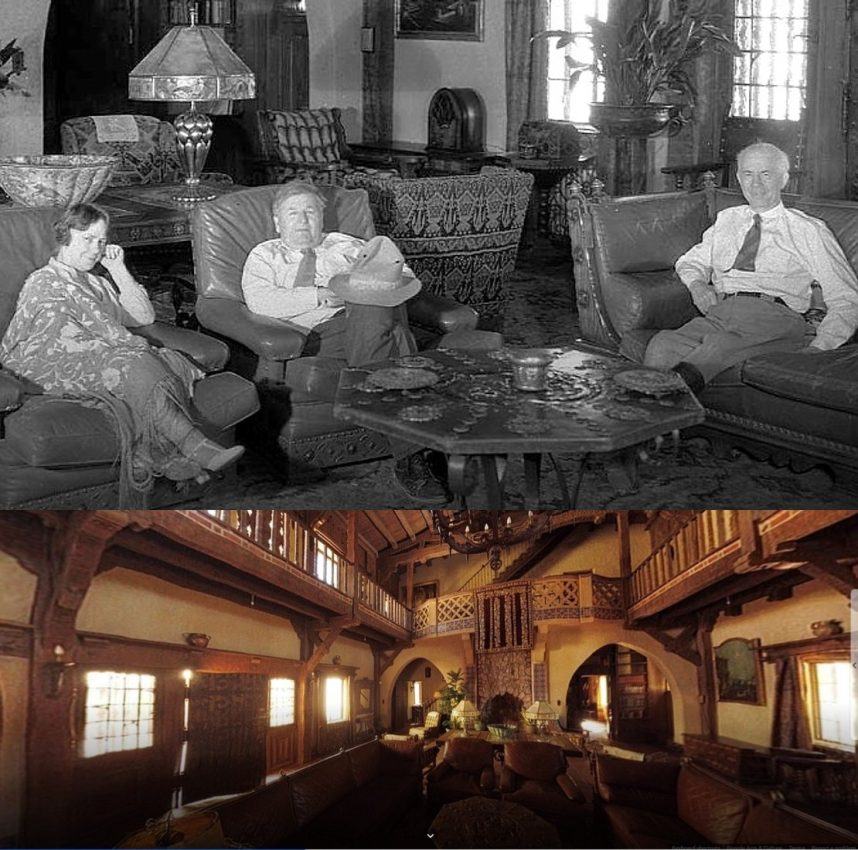

Once Johnson and his wife, Bessie, got to Death Valley and realized they were duped, she made the best of the situation. Albert had health problems stemming from an 1899 train accident that Bessie believed the desert air would help anyway.

So she convinced him to use their virtually worthless new land to build a dream winter getaway.

In 1922, they started with a horse ranch with living quarters for the couple and the 30 people (mostly Shoshone Indians) they hired to construct and run it. And even then, it drew national attention for its opulence.

The March 1926 issue of Sunset magazine noted that “Scotty is building a plant to generate electricity by the use of power that comes from spring water flowing from higher ground.”

That wasn’t a typo you just read. Though initially pissed about being had, Johnson remained fascinated by the colorful Scott and forgave him. When the magazine’s reporter called, the reconciled buddies convinced him that Scott was the owner and builder while Johnson described himself as “only [Scott’s] banker.”

The ruse satisfied both Scott’s need for attention and Johnson’s for privacy, and is how the legend of “Scotty’s Castle” was born.

In 1926, the Johnsons decided to upgrade to the $1.4 million mansion ($18.7 million today) that still occupies the land today.

No Secret Gold Mine

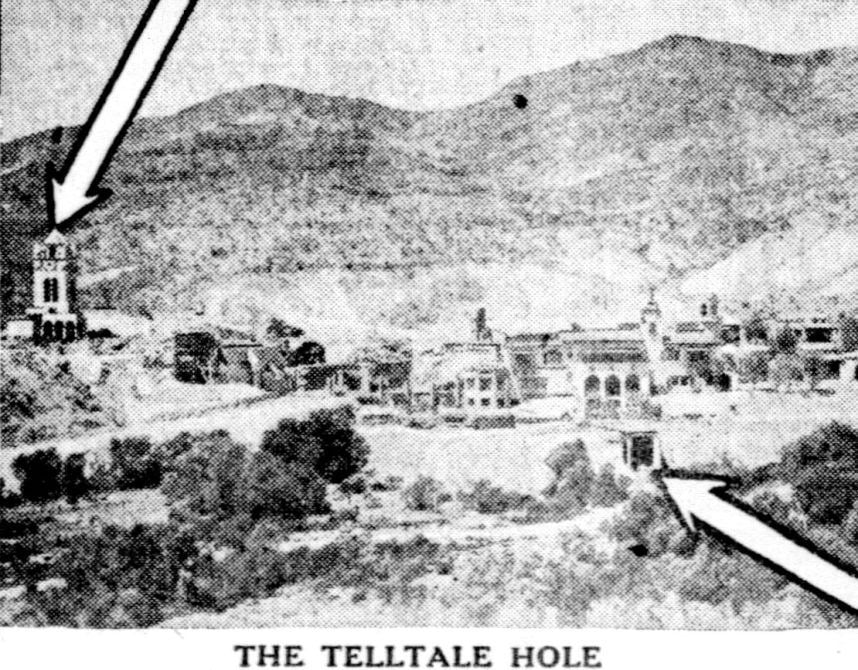

Do we even need to point this out? Apparently, we do, because a fanciful story originally published in the Nov. 15, 1931 edition of the Miami News still occasionally circulates.

It features a photo, captioned “The Telltale Hole,” that points to “a secret shaft entrance leading to the gold mine.”

“This is the first actual proof that there is a mine,” it read. “Ordinary photos do not show this opening because it usually is camouflaged by dirt and shrubbery.”

The reporter, who bought the story that Scott was the castle’s multimillionaire owner, asserted that secret digging and mining were conducted underneath the castle’s music room, where Scotty “set the mechanical organ in motion simply to drown out the telltale sound of the dirt machine in the shaft below.”

In reality, the hole was the entrance to a tunnel that made it easier for construction workers to remove excavated soil from the hilltop site. It’s likely that Scott himself planted this false story to interest more investors in his long line of nonexistent gold claims.

Castle Falls

The stock market crash of Oct. 29, 1929 robbed almost all millionaires of around half their wealth overnight. This included Johnson, whose insurance company, National Life, went bankrupt the following year.

Though construction on his mansion was already finished, several other structures in various stages of completion were abandoned, including a lavish pool. (The tiles intended for it remain stacked inside the mansion’s tunnel.)

Something almost as bad happened to the Johnsons three years later. That’s when President Herbert Hoover dedicated 2 million acres of government land to create Death Valley National Park, and the Johnsons discovered that this land included their own.

This was one of the only bad things that happened to the Johnsons in Death Valley that they couldn’t blame on Scott — at least not directly. An initial land survey conducted in the late 1800s turned out to be inaccurate. The Johnsons’ property was six miles farther up Grapevine Canyon.

While the Johnsons negotiated with Uncle Sam, Scott convinced them to rent out the rooms in their mansion to visitors, for as long as they could get away with it — a subject in which Scott was something of a Rhodes Scholar.

Bittersweet Victory

In August 1935, the Johnsons finally got some good news. President Franklin Roosevelt signed a bill allowing them to officially buy all the land they thought they had already purchased. And they did, for $1,900 ($43,500 today).

By then, however, they had retired to Hollywood, visiting Death Valley only occasionally. After Bessie died in a 1943 car accident, Albert stopped coming altogether. In failing health, he created a charity in 1947, leaving his property to the Gospel Foundation in his will. He died a year later.

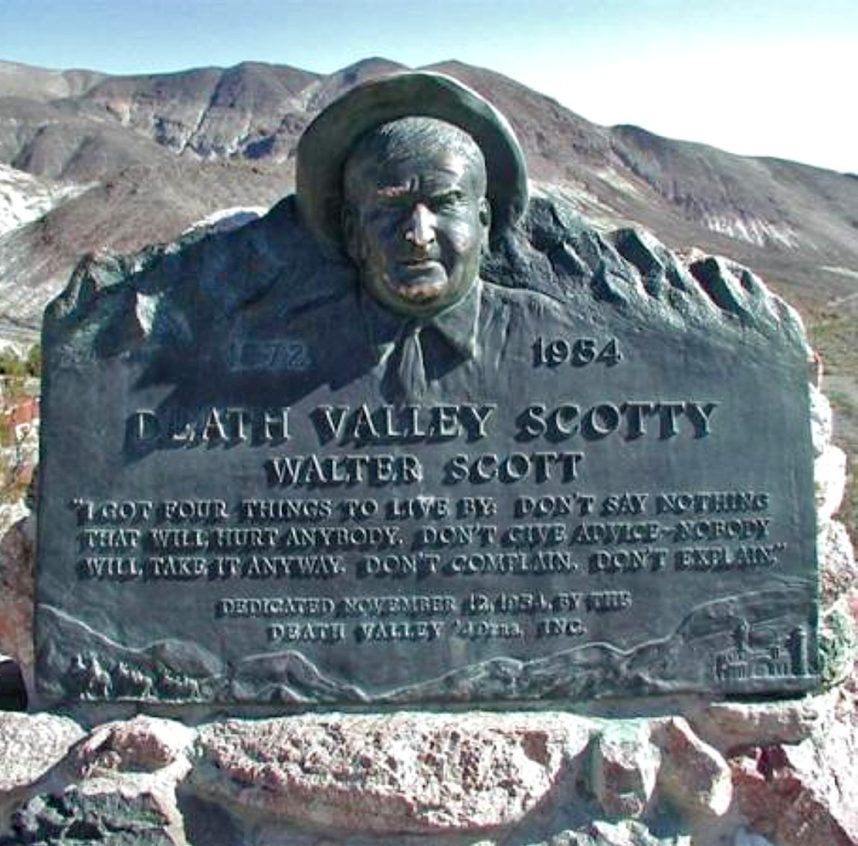

Another provision in Johnson’s will stipulated that Scott be allowed to reside in “his” castle for the rest of his days. When he died in 1954, “Death Valley Scotty” was buried on a hill overlooking the estate.

In 1970, the National Park Service purchased Scotty’s Castle for $850K from the foundation.

It remained the top tourist destination in Death Valley National Park for decades. But an October 2015 flood necessitated the closure of all roads leading to it. Then, in 2021, a fire destroyed the visitor center.

Restoration is underway and the castle is expected to fully reopen to the public by 2026. In the interim, seasonal walking tours of the property are offered. Through March 23, 2025, they run on select Saturdays and Sundays. Tickets are $35 per person, and space is limited to 20 participants per tour. For more information, click here.