Posted on: May 10, 2024, 07:04h.

Last updated on: May 9, 2024, 08:49h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on Aug. 7, 2023. Frank Sinatra died 26 years ago next Tuesday.

Frank Sinatra was certainly a driving force in the progress toward equality in Las Vegas. But contrary to a popular myth, the singer didn’t end the shameful legacy of segregation on the Strip. It took political action to do that.

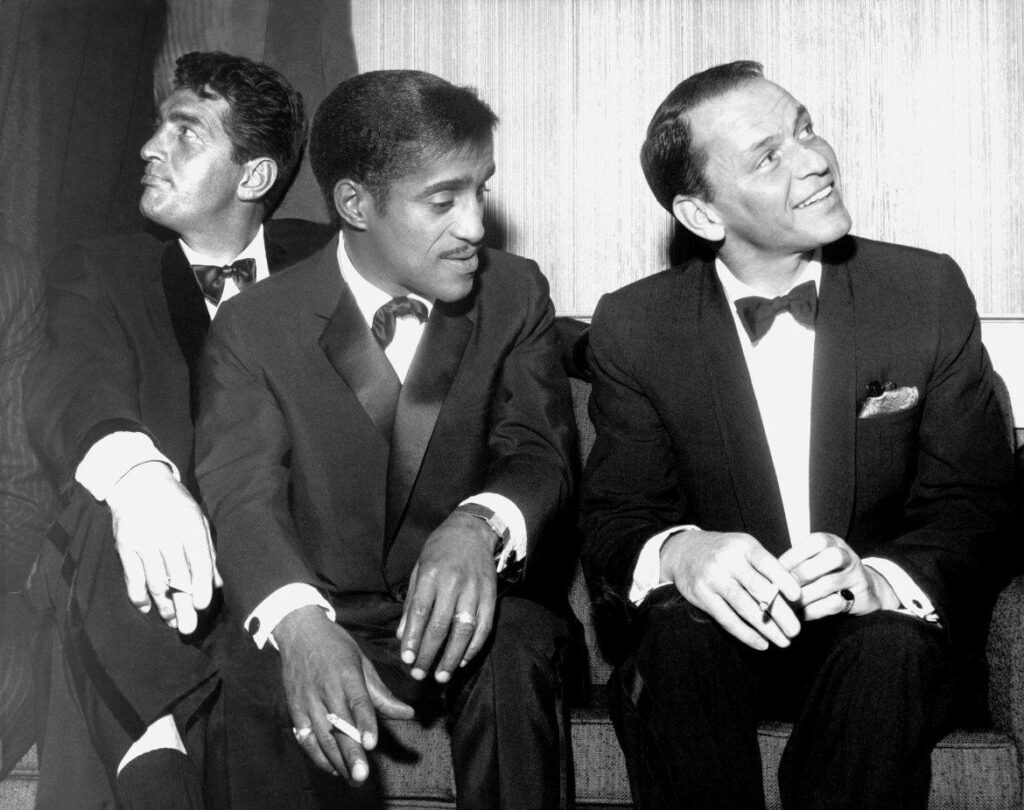

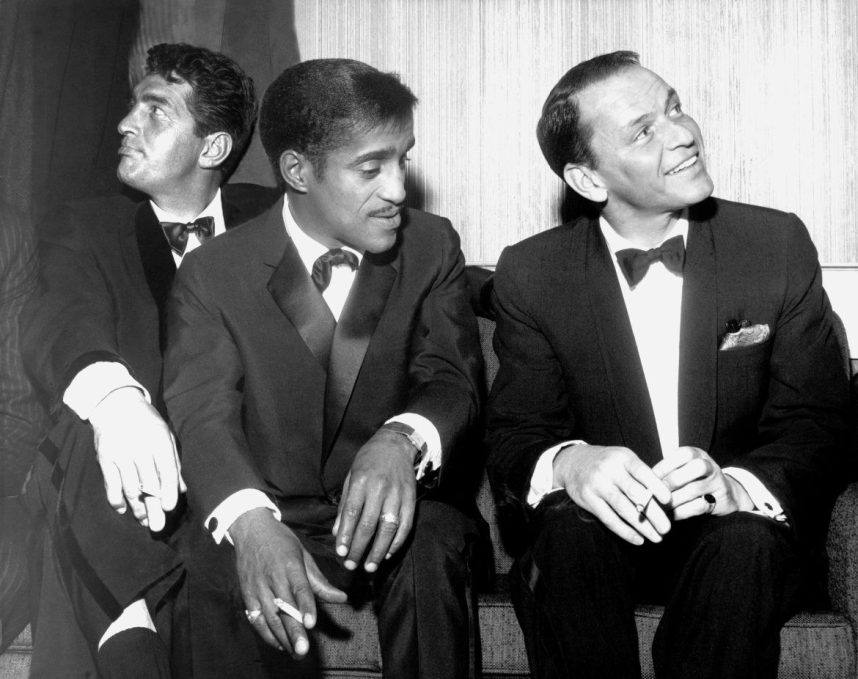

Around 1955, Sinatra refused to perform with the Rat Pack at the Sands unless the casino hotel allowed group member Sammy Davis Jr. to also stay there. In response, Davis was given his own suite.

At about the same time, Sinatra noticed that another of his friends, Nat King Cole, always ate by himself in the Sands’ dressing room, never with the other performers in the main dining room. When he was told why, Sinatra invited Cole to dine with him the following evening, making the “Unforgettable” singer the first person of color ever to eat in the Sands’ Garden Room.

Dozens of books and articles about Sinatra have repeated these two stories. They may be apocryphal, but let’s give Sinatra the benefit of the doubt. He was a white megastar who promoted civil rights at a time when few whites, especially rich and famous ones, acknowledged the plight of people of color.

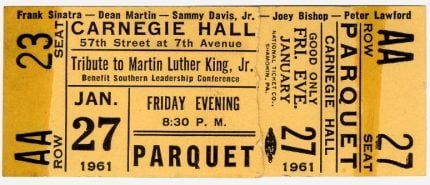

Sinatra and the Rat Pack headlined a 1961 benefit at New York’s Carnegie Hall for Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and he frequently addressed the evils of segregation during his concerts.

“As long as most white men think of a Negro first and a man second, we’re in trouble,” Sinatra wrote in an essay in the July 1958 edition of Ebony magazine. “I don’t know why we can’t grow up.”

The Injustice

Before 1960, people of color couldn’t stay, gamble, or dine in any Las Vegas casino hotels. This was true even of greatly admired Black headliners like Davis and Cole. They had to slip in through stage and kitchen doors to perform and leave the same way after taking their bows.

African-American Las Vegas tourists had to book rooms at boarding houses on the Westside, the historic Black community five miles northwest of the Strip. The most renowned was run by entrepreneur Genevieve Harrison, whose Harrison House is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Ol’ Blue Eyes bravely stood up against these policies. But did he really put an end to them?

Sinatra seemed to think so.

“It changed, it absolutely all changed,” he said in an interview conducted near the end of his life and included as a bonus track on a 2006 box set. “I did make some demands on some people and said, ‘Listen, if they all have to live on the other side of town, then you don’t need me, you just don’t need me.’ And I think a few other entertainers began to pick up on that, too, and they hollered, too.

“But I guess I was the biggest mouth in the town.”

What Sinatra was unaware of was the extent to which he was patronized by casino managers of the day. Because of his great fame and power, and his famously bad temper, he was habitually placated. Whatever he hollered for during his tirades was almost always granted … while he was around.

Whenever Sinatra, or other headline performers with the clout to demand integration, weren’t around, the old policies almost always returned.

At the time, Las Vegas catered to so many wealthy bigots from the Jim Crow South, it was referred to as the “Mississippi of the West” by Sarann Knight-Preddy, who in 1950 became Nevada’s first casino owner of color (not in Las Vegas but in rural Hawthorne, Nev.)

Though Las Vegas casino owners may not have shared the backwards views of many of their customers, they thought it bad for business to risk offending their sensibilities.

What Really Desegregated Vegas

On March 26, 1960, casino representatives and government leaders met with James B. McMillan, president of the NAACP’s Las Vegas chapter, in the coffee shop of the shuttered Moulin Rouge casino hotel to hash out an end to segregation on the Strip.

McMillian chose this location because the Moulin Rouge opened in May 1955 as the first desegregated casino hotel in Las Vegas. Though it wasn’t on the Strip and closed only six months later, the Moulin Rouge was the first casino where people of color could gamble or work front-of-house jobs.

At this historic summit, which became known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement, the casino reps reluctantly agreed to allow African-Americans to patronize their establishments and hold public-facing positions in them. This landmark decision eventually led to bans on real estate redlining and discrimination in all employment and business licensing.

And what convinced the casinos to cave?

Fear, plain and simple. The Moulin Rouge Agreement occurred one day before a giant civil rights march McMillan had scheduled on the Strip to protest segregation there.

And that would have been bad for business.

“The black community fought for and won the basic human right of using public accommodations, not an entertainer who was able to get his friend a room for a few nights,” Claytee White, director of the Oral Research Center at UNLV, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in 2015.

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Visit VegasMythsBusted.com to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.