Roman Weidenfeller’s face creases and his voice lowers, almost wincing at the recollection. “Maybe it is 35 when it starts. You are not as quick, not as fast as before with the reactions.” He is discussing his decline as a goalkeeper. It is a painful memory.

“You feel it, you have saved the ball,” adds Weidenfeller. “But then the stadium is crying and you are thinking, what has happened? The ball is in. This is the feeling. Normally, it is your ball and you save it. But you don’t save it. It is the last seconds. It is too late.”

The former Borussia Dortmund goalkeeper is wondering whether his old Bundesliga rival and international team-mate Manuel Neuer is going to rediscover the level that saw him become the best goalkeeper in the world. At 37, it is going to be a challenge.

Neuer is back in the Bayern Munich team after missing almost a year of football following a skiing accident in December. Some thought he would not return. But with Euro 2024 in Germany next summer, the incentive is there to continue for club and for country.

It is 16 years since Neuer made his Champions League debut, nine since he became a legend. His performances in winning the World Cup for Germany in 2014 earned him a place on the Ballon d’Or podium, the only goalkeeper to manage that in the last 17 years.

It is not just his quality. There are many greats in this game but how many active players can claim to have changed the way that the sport is played? With his confidence on the ball and, most significantly, his ability to race off his line, Neuer is in that bracket.

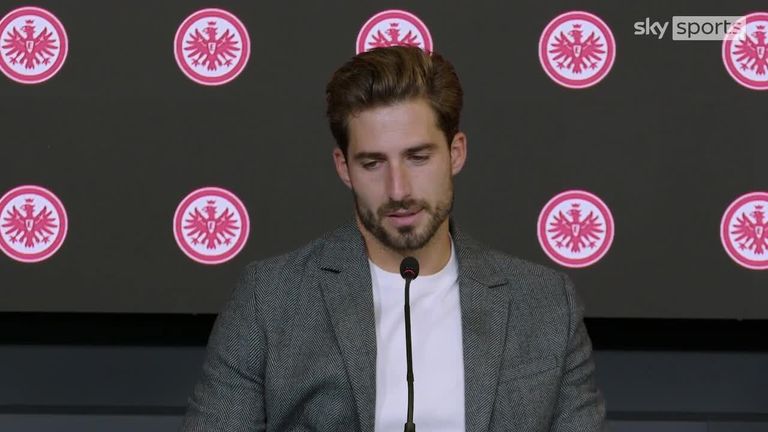

Eintracht Frankfurt’s Kevin Trapp was one of Neuer’s understudies in the Germany squad at last year’s World Cup. Neuer did more than inspire his goalkeeping, he changed it. “I grew up with Oliver Kahn and Jens Lehmann, their way of goalkeeping,” he explains.

Trapp believes Neuer changed goalkeeping in 2014. “He took it to a whole other level. Since then, everybody wants to be like Manu. Before, you always wanted to be a striker to score goals. That speaks for itself. You could see what else goalkeepers were capable of.”

For four seasons out of six between 2010 and 2016, Neuer came out to sweep up behind his defence more than any other goalkeeper in the Champions League. Only the emergence of Ederson and others like him mean he is no longer such a statistical outlier.

But they are an indication of his influence. The game has changed dramatically during his career. In his final season at Schalke, there were 2919 passes attempted by goalkeepers inside their own half in the Champions League. That figure reached 5537 last season.

The role of the goalkeeper has expanded, as Trapp explains.

“Before, it was just about being on your line, saving balls. Now it has become, I will not say more difficult, but, more complex.” Now, the goalkeeper is not just a stopper but a sweeper and a playmaker. “Coaches ask more of the goalkeeper now,” he says.

“Football became very modern so you need the goalkeeper to be the 11th player.” It can make the difference. “You are able to clear things before they even happen if you are good at anticipating, if you help the team by going for crosses, if you are good with your feet.”

Neuer, at his best, did all of those things and he did them better. It could get him into trouble. But the accomplishments of him and his teams suggest that it was a calculated risk that paid off. “It helps more often than it causes a goal,” says Trapp.

Can it be taught?

“Manu is Manu, of course. But you can learn it,” he adds.

“You just need to have the courage to be interested and open-minded. You need a coach who supports you. You also need a coach who accepts that if there happens to be a mistake that is OK, it is a process and you learn from your mistakes.

“It does not mean that you will be at the same level. That is why Manu was for such a long time the best goalkeeper in the world.

“There are little details that make the difference between world-class and, let’s say, a normal goalkeeper. I am pretty sure that not only for me but for a lot of goalkeepers who came through in that generation, Manu was their role model, 100 per cent.”

All things come to an end, however.

Trapp has seven caps for Germany, the most recent of them coming in June while Neuer was injured. With Marc-Andre ter Stegen long since established as Barcelona’s No 1, there is competition at international level. Neuer must show he is the same goalkeeper.

There was a smart save to deny Marco Reus in the recent win at Dortmund, a win that brought Neuer his second consecutive Bundesliga clean sheet since his return. His old rival Weidenfeller thinks Neuer has nothing to prove in terms of his legacy.

“He is in that [group] with Schmeichel, Kahn, Buffon. One of the biggest goalkeepers in the world.” But Weidenfeller knows from his own experience that Neuer is not just battling Trapp and Ter Stegen. He is now in another fight. One that nobody can win.

“Of course, you always work at your reactions on the machines, with the new technology. But the biological clock is ticking. It is. And you always need the rhythm of every seven days, or even every three days in the Champions League and the Bundesliga.

“But when you are injured and lose that rhythm, and you are coming back like Neuer just now, it is very complicated. I cross my fingers that he will do it and play next year at the European Championship. But we will see how his body feels after Christmas.”

If he can stay fit, if he can show that the old swagger is still there, Neuer could yet earn himself the ending that his career deserves. “He has to look what the body is telling him,” says Weidenfeller. “Of course, he has the chance. But I think that is a long time away.”