At the start of this year, Pep Guardiola remarked, “Finally, Manchester United is coming back.”

Yet after a derby undressing on Sunday afternoon was followed by another thumping by Newcastle, the only returning cycle in evidence for the Old Trafford side is the one where any shoots of promise have been replaced by the familiar feeling of it all unravelling.

Louis van Gaal, Jose Mourinho and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer will offer a knowing nod. The latter encapsulated just how rapidly the atmosphere can shift at United in one, piercing sentence when discussing Ralf Rangnick, who had succeeded him on an interim basis.

“The club he found in November 2021 was different from September 2021,” Solskjaer said.

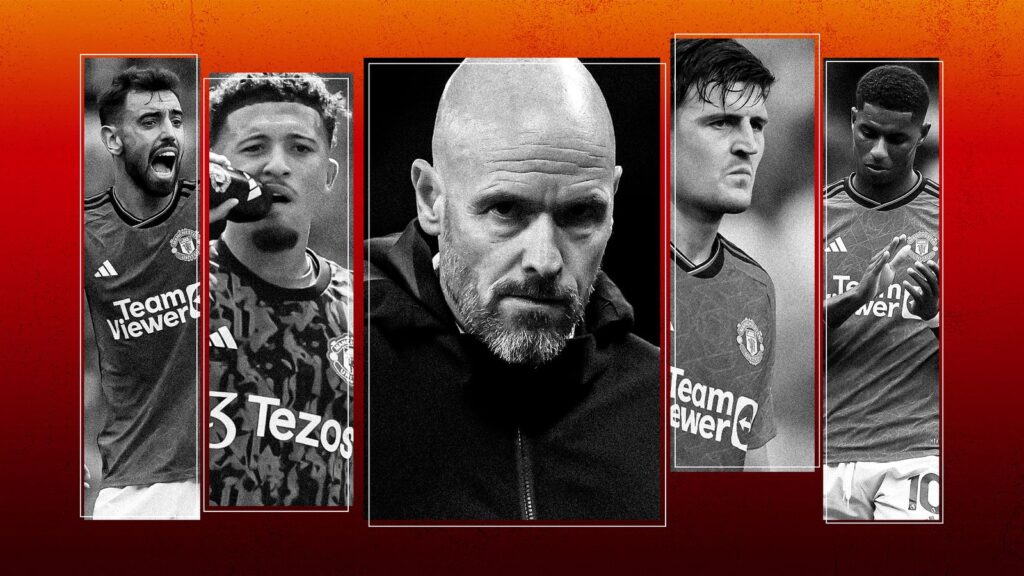

Two months and bust. Now it is Erik ten Hag’s initial positive work, achieved during a turbulent debut season in charge, which is being shaded by a sharp dip – albeit not one that has transpired so quickly.

United have been regressing since February, but the real scare is the deterioration in this campaign. It is an indictment for the club that the embarrassing numbers only scratch the surface of their disarray.

United have suffered the most defeats in their opening 10 league games since 1986/87.

Only Bournemouth (12 per cent), Luton (eight per cent) and Sheffield United (four per cent) have spent less time in a winning position across those games than Ten Hag’s side (13 per cent).

They have managed to create just 18 big chances.

As damning as those stats are, the data is not able to capture the off-pitch environment colouring United’s on-pitch struggles.

The souring of relationships from the handling of the Mason Greenwood situation lingers. The club have exiled Jadon Sancho, a £73m asset, from the first team after failing to resolve a stand-off between him and the manager.

Antony is facing assault allegations, which he denies. There would be few dissenting voices to the opinion that the winger, signed for £86m, has turned in performances that suggest there should have been a decimal point in his transfer fee.

November will mark a year since United embarked on a strategic review “to enhance future growth” that has led to endless uncertainty, now culminating in the expectation the football operation will be overhauled should Sir Jim Radcliffe’s INEOS obtain a 25 per cent stake in the club.

A “business as usual approach” has been undercut by the knowledge over the past 12 months that, as one source put it, “change can come fast, without anything we could do about it and without really knowing about it”.

United’s unconvincing displays – there is no discernible playing identity – are a mirror of their lack of surety as a club.

While Ten Hag has to shoulder responsibility for the indistinctive and unremarkable football we have witnessed, the continual boom-to-bust cycle and wider issues at the club stretch straight to the top and the ownership of the Glazers.

United insist they have learnt from the mistakes of the past, but a key one was designing an entire blueprint based on whims of the manager, rather than a vision for the club which would then inform who the right candidate should be in the dugout.

We have seen it again with Ten Hag, and to greater effect than ever before.

Casemiro is the only major signing the Dutchman did not actively and heavily pursue, with the midfielder’s representatives pitching him to United. The staggering outlay on Antony, Mason Mount, Rasmus Hojlund, Lisandro Martinez, Andre Onana, Tyrell Malacia, Christian Eriksen, plus the loan signings of Wout Weghorst and Sofyan Amrabat were all driven by Ten Hag.

The club have insisted every permanent signing was on their scouting radar separately from the manager’s desire to recruit them. It is unthinkable that United would have sanctioned circa £310m on the same players – the majority with a thick Eredivisie background and having a pre-existing relationship with Ten Hag – under someone else’s watch.

It is inarguable that Ten Hag’s transfer decisions have been fiercely backed, even if the outcome has been unsuccessful as was the case with Frenkie de Jong. Harry Kane was the only player coveted by the 53-year-old that was not seriously chased due to the fact Tottenham did not want to sell him to a Premier League rival and a move was not financially viable.

This is where the idea of what support entails becomes pivotal. Is giving the manager almost everything he wants the smartest way to run a football club, or it is wiser to operate in the market based on the club’s needs and ultimate stylistic vision?

It is an enduring myth in football that some of the best modern managers are responsible for all signings. That is what an excellent recruitment structure delivers: Guardiola is the first to credit Txiki Begiristain for building his Manchester City empire, Edu worked for a year to get Declan Rice over the line for Mikel Arteta, and it was Michael Edwards who directed Jurgen Klopp away from Julian Brandt towards Mohamed Salah.

Even the foremost managers understand they cannot be sporting directors and chief scouts – nor should they need to be. Ten Hag’s premier work at Ajax was born out of a stable, clear structure (and look at the state of the Dutch club now in absence of it).

In an exclusive interview with Sky Sports News last April, Rangnick warned: “I know that for the future, and I think even more so for a big club like Manchester United, you can’t put all those jobs and tasks and the whole responsibility only on the shoulder of one person – on the manager. I’m not sure if this can be dealt with by one person, no matter how good he is.

“I know Liverpool, Manchester City and Chelsea also have smart people who take care of recruitment, scouting, the medical department… I think this is also an issue for our club, where they have to pay attention to.”

Under football director John Murtough, United have tried to remedy their transfer ills with a new system over the past 18 months. However, we are yet to see proper evidence of intelligent buys being made for the manager, or an uptick in selling well.

Murtough has a great relationship with Ten Hag, is well liked, and has good intentions. He has been hamstrung by historic bad decisions from the Ed Woodward years, which United are still paying the costs of – as well as Financial Fair Play regulations.

Employees enjoyed CEO Richard Arnold’s approach of empowering people and departments while creating a happier work environment, but many staff were disillusioned by the mishandling of the Greenwood situation and the wording of the final club statement on the matter.

That United initially intended to keep the striker was another sign of Ten Hag’s power: had the manager and football operations decided they did not want him as part of the team, that would have been the end of the matter. The way Sancho has been dealt with is illuminating in that regard.

There are too many off-field explosions at United, which prompts questions of the club culture and leadership.

There is also the understanding that some good people are trying to undo a decade worth of poor choices and decay that stems from the very top of the club. It cannot be helpful that for a year while the takeover saga has hung heavy, there has been anxiety over potential job losses.

For the current set-up at United, despite alarming non-performances and results, there is absolutely no doubt in the plan and Ten Hag. The belief is there was enough evidence last season, with the club being returned to the Champions League, ending a near seven-year trophy drought, and finishing with their highest points total in five seasons, to indicate Ten Hag can improve United’s standards and playing structure while delivering silverware.

Arsenal’s faith in Arteta has been used as an example by the club but the Gunners have a superior operating structure, the playing identity was evident even when results were not forthcoming, the profile for recruitment has been crystalline, and they do not hesitate in taking big financial hits – like cancelling contracts – for the greater cultural good of the team.

Some of the upheaval in this campaign for United can be attributed to injuries, when at one point 16 players were unavailable but the manager never used it as an excuse. He is yet to field what he deems his first XI. The absence of Luke Shaw and Martinez has killed the left side for United, affected their balance, and also impeded Marcus Rashford’s game.

The England international needs to claim more responsibility as well though, and a return of one goal in 13 games while receiving all the necessary support in terms of coaching and trust is not a good look.

It has to be said that United are not giving him and Hojlund much to work with in terms of chance creation, although the latter has proven to be a willing runner, wants to win his duels, and perhaps if anything is trying to do too much to remedy going seven league fixtures without scoring.

Ten Hag spent last season trying to restore the basics at United: defensive structure, physicality, pragmatism and feeding their counter-attacking strengths.

The planned evolution was to make them more comfortable in possession and “the best transition side in the world,” with the signings of Mount and Onana in particular aiding both aims.

Neither has happened yet and Ten Hag admitted to Sky Sports News both players have had a harder time settling in due to the inconsistent state of the team, although the goalkeeper has turned in three stronger performances on the spin.

“It is not only about them, it is about the total team,” he said. “You highlight them and I know why you highlight them because they are new but it is unfair.

“No one in this moment are reaching the levels they should be.

“Of course, it is harder for the new players to integrate [because United are not reaching the expected standards yet] but the players last season know better the rules, the principles so the new players have to know them through the routines in the meantime.

“They have to know each other but when they have to play in a different line-up it is difficult but, I am confident.”

Ten Hag’s message to his players amid the unconvincing performances and unrelenting noise that surrounds the club has been to “stay on the same page and stick to our plan”. It is increasingly hard from the outside to decipher what that is. It is understood the 83 principles – a large portion centred around discipline and work ethic – the manager introduced in his first meeting have not been altered.

There has been a question mark around the psychology of the squad and how quickly confidence gets sapped after a defeat.

Ahead of the Carabao Cup final in February, Bruno Fernandes offered to Sky Sports: “It’s up to us to keep going, up to our qualities, up to what we have been doing really well, and so it is about us now to carry on because it’s easy to forget the good results we have done whenever you lose a game. So it’s us about us to carry on in doing our best because we don’t want people to forget how good we are.”

It is the players who need to remember, and fast because the victories over Barcelona, Liverpool, Manchester City and Arsenal last season feel like a trick of the mind.